Problems of Feedback in U.S. Governance, the widespread political denial of principle

Examples of poor feedback:

This year, the government will spend at least $890,000 on service fees for bank accounts that have nothing in them. At last count, Uncle Sam has 13,712 such accounts, each containing zero dollars and zero cents. These are supposed to be closed. But nobody has done the paperwork.(1)

Clarence Prevost, the flight instructor assigned to Moussaoui, began to have suspicions about his student… Prevost was confused as to why Moussaoui would seek simulator time if he lacked basic plane knowledge. After some convincing, his supervisors contacted the FBI, who came to meet with him… Some agents worried that his flight training had violent intentions, so the Minnesota bureau tried to get permission (sending over 70 emails in a week) to search his laptop, but they were turned down. FBI agent Coleen Rowley made an explicit request for permission to search Moussaoui’s personal rooms. This request was first denied by her superior, Deputy General Counsel Marion “Spike” Bowman, and later rejected based upon FISA regulations (amended after 9/11 by the USA Patriot Act). Several further search attempts similarly failed.(2)

WASHINGTON (AP) — An interim report released Tuesday by House Republicans faults the State Department and former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton for security deficiencies at the U.S. diplomatic mission in Benghazi, Libya, prior to last September’s deadly terrorist attack that killed Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans. Senior State Department officials, including Clinton, approved reductions in security at the facilities in Benghazi, according to the report by GOP members of five House committees. The report cites an April 19, 2012, cable bearing Clinton’s signature acknowledging a March 28, 2012, request from then-U.S. Ambassador to Libya Gene Cretz for more security, yet allowing further reductions.(3)

The above quotes are examples of a problem of feedback in U.S. government processes. They are examples of government processes that are unresponsive to the feedback provided by the real world. Such lack of responsiveness is symptomatic of authoritarian, brute force, systems of governance where power flows from the top down, denying known principles of sound governance. And, these types of systems tend to be standard operating procedure (SOP) for many government agencies, based on a lack of sophistication and refinement of US political processes. They cause financial waste, they prevent followup on terrorist suspects, and they generally produce agencies that fail to either perform their mission well or serve the citizens they were created to serve.

Democracy at the macro level, authoritarianism at the micro level

It is a common misconception to think that, because the U.S. has a democratic system of governance, it will be responsive to the people. At the macro level, where voters have some impact on their representatives, this is true. When the voters get frustrated enough, they can create enough pressure for the representatives to pass or rescind a law. But the laws that create government agencies to address problems usually create hierarchical agencies, responsive to appointed officials and budget appropriations. By nature, they are not responsive to real-world feedback.

In the case of the FBI or the State Department, the director is appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. This appointment is often based on years of public service that would provide qualification, but it is also often made as a reward for political loyalty. Regardless of whether the appointment is based on skill or favoritism, once the appointment has been made, the director is called into frequent meetings with the president and given instructions that become the director’s top priority.

Feedback from below is always a lower priority by nature of the director’s focus on loyalty to the concerns of their superior. So, in the case of Rowley’s request for investigation of Moussaoui to her FBI supervisors and Ambassador Gene Cretz’s request for more security in Libya, the legal and political pressures from above prevented genuine real-world feedback the agency needed to successfully perform its mission.

Often the response is one of brute force: fire the head of the agency, or a “fall guy” within the agency. The President and the Congress do not generally involve themselves in the micromanagement of an agency or its processes. The system can be compared to having an on/off switch on the furnace of your house, rather than having a thermostat that senses the room temperature and provides feedback through a component of the heating system. In such a case, the house may get too hot or too cold, depending on whether the owner is home and how often he personally checks the temperature of the room. Of course, in government—the President, or the Congress—things are rarely checked until a crisis is reached to force some type of reaction.

Limit Switches: Feedback that overrides manual operators

Like the thermostat developed to provide feedback to a home heating system, many technologies rely on good systems of feedback that prevent self-destruction of the system. In engineered products, there are thermostats, pressure switches, and other limit switches that keep machines operating within stable boundaries.

Many cars, lawnmowers, and other engines have a governor on them that prevents them from running too fast and blowing up. This governor overrides the throttle control setting of the operator. In other words, the system is designed in such a way as to not let the operator act outside certain limits. My car has a setting that limits its speed to 138 mph regardless of whether the driver keeps the gas pedal fully depressed. This governor may frustrate a driver that wants to push the limits of the car in the quest for greater speed, and some car owners disable such governors and end up destroying their engines.

The U.S. Constitution as a Limit Switch

The U.S. Constitution was an attempt to “engineer” the U.S. political system in ways that placed limits on the behavior of all three branches of government. It was one of the more remarkable political documents ever devised, in that its creators attempted to prevent the U.S. government, or any component, from having absolute control.

The system of “checks and balances” they devised was an attempt to limit power through its distribution, and to distribute that power as widely as possible, ultimately distributing the power equally among all voting citizens, who were to be the last line of defense against the failure of the branches of government to check one another, and for the states to check federal power. Unfortunately, these checks were inadequate as they did not prevent the rise of factions of citizens pooling economic interests or responding to social fads. And, without clear limits, like a cut-off switch at 138 mph, the various branches of government have failed to check one another in ways the founders intended, but instead have found ways to remove the limits designed into the system based on founding principles. These failures and circumventions are discussed in detail in my book, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, Version 4.0.

The market as natural feedback

In the market, the “law of supply and demand” is a natural mechanism that raises and lowers prices of goods depending upon supply and demand. In perfectly competitive markets there are no sales without feedback. A seller will not be able to sell his product unless his price is set at the level buyers are willing to pay. Simply because he controls ownership of a product, the seller is unable to make any sales or profits unless he is aware of market prices, which are a form of natural feedback.

Not all markets are perfectly competitive, and not all markets are simple exchanges, but at their core there are feedback mechanisms. Even the Soviet system of centralized economy could not continue to build warehouses for storage of products citizens did not want (like an ongoing budget to produce a record album popular in 1947). But in the case of the Soviet system, the market feedback was so ignored by the “seller” that eventually the system reached a critical limit and collapsed.

Engineered feedback for home loans

Home loans are not simple market transactions. If I sell my house at a market price of $200,000 and receive a cash payment, the transaction is done. That is a simple market transaction. However, if the buyer goes to the bank and gets a loan, and the bank pays me, a new micro-system somewhat analogous to the creation of a new government agency has been established within the basic market. This micro-system, the home loan, requires a different type of feedback to ensure that the bank will get paid by the borrower.

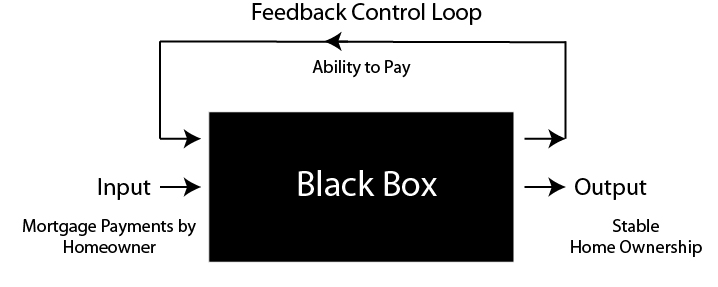

In the above diagram, the black box represents the home loan feedback system. A loan will not be given to the borrower unconditionally. A long history of mortgage lending has refined its system of feedback so that a loan will not be issued unless certain criteria are met, for example:

- A down payment of 20% that guarantees minimum equity.

- A monthly payment not to exceed 28% of borrowers after tax income that provides some assurance of ability to pay.

- A credit history that shows the borrower has consistently paid on other loans he has taken.

- An evaluation of any other loans the borrower has outstanding to ensure he is not overextended.

In a bank with a proper feedback system, home loans that do not conform to these established lending principles should not even be overruled by the president of the bank, unless the president personally guarantees the loan, or unless the borrower has some other form of insurance that will guarantee payment in the event of a default.

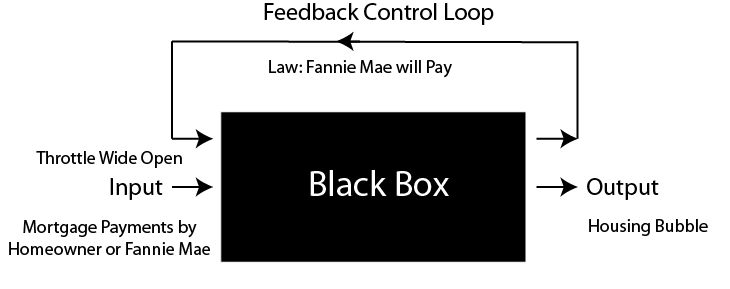

The 2008 mortgage bubble, a brute force approach

Brute force systems of governance often fail to employ or respond to sound feedback mechanisms. The 2008 mortgage bubble was caused, in part, by a government intervention that guaranteed home loans to banks when the borrower failed to meet proven lending criteria. This intervention was caused by political lobbies that sought to use the power of government to guarantee loans to unqualified borrowers in order to fuel more lending and construction. This guarantee, acted like overriding the governor on a car and holding the pedal to the floor:

The housing bubble was an example of legislation that ignored sound principles of lending knowledge in an attempt to coerce a desired political outcome. In a sound system of governance, knowledge about loan payment principles and feedback from them could not have been ignored, but in the current U.S. system where fashionable rhetoric, often masking special economic interests, trumps principles, sub-agencies like Fannie Mae end up responding to their hierarchical superior rather than real world principles.

Widespread political denial of principle

I began this article with quotes about the political denial of feedback in the FBI and the U.S. State Department, and just cited an example of a willful overriding of principle through federal home loan legislation. Unfortunately, these are not exceptions to the rule but too often the norm. We saw other mini-bubbles created by “cash for clunkers” and used home appliances. We have federal school loan guarantees that have caused an “education bubble” and inflated tuition prices, not unlike the inflated real estate prices caused by guaranteed home loans. These bubbles occur because the law of supply and demand will inevitably trump brute force attempts to manipulate demand, supply, or prices.

We often lay this widespread denial of principle at the feet of Congress or the president. But can we believe that they are not aware of centuries-old principles, like the sound criteria for home loans? Are they acting in ignorance? Of course many of the voting citizens who believe the rhetoric that it is fine to pass laws that ignore principles are genuinely ignorant, but many of the legislators, and the president himself, have economic interest groups to respond to. This is why they willfully promote political policies and laws that violate established principles.

The chief motive of any normal political official, government appointee, or bureaucrat is the pursuit of his own personal interests. Except for extreme cases of altruism, such as that portrayed by Jimmy Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, legislators, elected officials, political appointees, and employees in government agencies put their own interests ahead of the public interest.

One way to improve on the percentage of “public servants” who actually put the public interest above their own, would be not to pay them any salaries, but then there would not be enough people doing the work of government. Therefore, systems of feedback and sound principle must be turned into laws that prevent, or a least thwart, the sidetracking of public funds in ways that support private interests, whether individual interests or group interests. Neither the interests of private individuals, nor the interests of factional groups like corporations, labor unions, or government bureaucracies are identical to the public interest, and ways must be developed to keep such private interests within the boundaries of public interest established by sound and known principles.

Government agencies and the denial of principle

We often consider factional interests like corporate lobbies and labor unions to be the primary interests controlling government, and to some extent these groups tend to control portions of the Republican and Democratic platforms respectively. However, as intransigent and unpatriotic as these factions seem, there is a largely silent force helping to create out-of-control government. This force is government agencies themselves, and their resistance to change and public feedback because of their insatiable desire to increase departmental budgets and improve the life situation of employees.

It was said that British Department of Colonies continued to grow at 6% per year, long after most of the colonies had been given independence. There were new reasons for funding provided by the bureaucrats related to monitoring the newly independent states, or creating better statistics for the historical understanding of the colonies of the past. Be assured that no one in the government agency was asking to be fired from their job or have their budget reduced because the original purpose for their agency no longer existed.

No government ever voluntarily reduces itself in size. Government programs, once launched, never disappear. Actually, a government bureau is the nearest thing to eternal life we’ll ever see on this earth!—Ronald Reagan(4)

Conclusion

One of the most important tasks of social reform today is the creation systems of governance that respond to feedback from the real world and are not captive to the authoritarian whims of their leaders, or of those who appointed their leaders. Whether we want to believe it or not, government is a form of machine, a human creation, that can perform its job well, like a finely crafted Swiss watch, or be motivated by the brute force of power that underlies the nature of government and act politically until a crisis forces a change upon it.

Our job, and my reason for writing Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, Version 4.0., is to study, learn, teach, and implement core principles of sound governance in our society that has largely ceased to understand or respect the very principles necessary for its continued survival and the happiness of its citizens.

One of the primary goals of the contemporary engineer of government is to create government mechanisms that both limit the actions of those in charge when sound principles would be transgressed, and to limit the lifespan and size of government agencies based on effective feedback related to the accomplishment of their stated mission.

Democracy is not some magical system that enables anyone to lobby their legislators and political officials in order to get something from government for themselves. The role of government is a public purpose, and current political processes assure its failure in accomplishing that role. Unless, government and its agencies are governed by processes based on feedback that ensures a public outcome, we can expect its continued support of private interests, dysfunction, and eventual collapse. Sound political principles, principles that would restore U.S. governance to a public purpose, are well known.

While most voters lack knowledge of these principles, they are not unknown to our civilization. Our governments can be improved. We have the know how, but so far we have lacked the will.

Law changes slowly, because it is desirable for law to be stable. Responsiveness to feedback is actually undesirable, as well as difficult. You don’t want laws against assault to be softened if there are too many assaults. Bureaucracies are creatures of law, and are therefore top-down and unresponsive.

Private, free economies that operate on the basis of voluntary exchange are responsive by nature. This is also highly desirable.

The problem is that we should not be trying to do things that require responsiveness through politics (law). As you rightly point out, it is a recipe for failure.

-dgl-

Don, I get your point about the responsiveness of law. You are primarily referring to the issue of the arbitrary laws being passed by responsiveness to special interest pressure. This is obviously not the type of feedback I was referring to. Rather, for laws I was referring to principled feedback learned from historical lessons. For example, feedback learned from centuries of home mortgage lending would have provided the law writers with principled boundaries their mortgage-bubble legislation ignored. Thus it is not feedback from spontaneous pressure that we want, but feedback from sound principles. In that case the pace of law would change more slowly, and the system would become more stable.

But, I was also talking about feedback in government agencies from the world they are supposed to serve, and why and how departments like the State Department and the FBI have had failures of gross negligence from ignoring this feedback; and, why it is the nature of these agencies to ignore it.

Thanks Gordon. Well-stated. Brief comment: De Toqueville’s first volume of Democracy in America was in part an effort to understand why the American Revolution seemed to work, resulting in relative stability, whereas the Frence Revolution gave rise to one disaster after the other for 40 years. He argued that this was due not only to voluntary associations and civil society institutions, but to religion and a pervasive ethos rooted in moral principles. Feedback is not entirely independent of the quality of the character of “the people”.

Good point Tom. I would have to consider that as “positive feedback”–meaning a cultural basis for creating ways to serve the public interest better. Whereas, limits of constraint on government behavior would be largely “negative feedback,” designed to prevent government from going off a cliff.

Many have lamented the difficulty in generating and sustaining what you call “positive feedback”, e.g., today’s WSJ opinion on Donald Kagan, retiring at 80 from classics at Yale. Democracies rise on some foundation of public virtue that sustains the res publica during a golden age but over time decline sets in and the corrupted popular will. the demos, cheers on its own demise. Your call for giving attention to positive feedback is well taken, but it may become an increasingly scarce resource

Plato explained 9 reasons why democracies fail, and we are experiencing many of them. Aristotle and Jefferson thought only agricultural societies, where each person was self-sufficient, could support democracies. More recently, scholars like Jean Bethke Elshtain have argued that Protestant teachings that inculcated self-responsibility allowed Western Democracies to rise.

One reason I use the language of engineering and feedback (besides the fact that I also have an engineering degree) is that these terms often better transcend religious and cultural differences and we need to find post-modern modes of communication to discuss issues like “virtue” and “civility” that often get relativized away as the “philosophy of dead white men,” rather than as something essential for a society to function.

Societies are systems, and many of the terms related to the design of systems apply to societies as well. I think these terms transcend the political rhetoric we hear in the popular media, as well as the relativism ascribed to inherited values. When we can analyze society as a system, we can make a determination as to whether a particular value or behavior has a positive or negative effect on the system.