Completing Civil Rights: Ending Structural Racism by Removing Race from Institutional Data and Policy

The United States has seen the evolution of civil rights from the abolitionists before the founding to the Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s that gave full legal equality to all races. These civil rights are negative rights: equal protection under the law to freely pursue life, liberty, and happiness. Most individual Americans have come to accept these rights, and we live in a society with greater intermarriage, mixed housing, and colorblindness in the market.

However, our governments and many social institutions have never reached the stage of treating all people as equals. This is the result of racial data collection and policies that treat people differently based on such data. Elimination of questions of race and ethnicity on driver’s license and passport applications, census forms, university applications, and health questionnaires would mark the final legal hurdle to overcoming racism by social institutions. Racism in social institutions is what is called commonly called “structural racism.”

Today identity group politics has become the latest face of structural racism, and it is rooted in social data and policies that treat people differently depending on answers they provide on government forms. Identity group politics is not rooted in “negative rights” but “positive rights.” Positive rights are not freedoms to pursue a goal, but the right to be given something. When positive rights are provided by public policy, they are considered “entitlements.” Identity group politics argue for entitlements based on race, ethnicity, or some other factor, rather than a person is entitled because they are a human being like everyone else. Thus identity group politics become tribalism and a war over the resources of the government.

The US Founding Sought an End to Identity Group Politics

The US Founding is based on one preeminent principle:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

In their Declaration of Independence, the Americans were declaring they were no longer willing to be the subjects of a remote king who “taxed without representation” and whose government monopolies like the East India Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company would force independent entrepreneurs out of business.

Colonists and settlers in America were from many social and cultural backgrounds, and many of the 13 colonies had “established” religions. This meant that, like the idea of Sharia law, the doctrines of the established religion would be enforced by the government, that “heretics” could be punished by the government, and that the taxes collected from everyone could be used to support the indoctrination of everyone in the official religion. In Virginia, New York, Maryland, North Carolina, and South Carolina, the Church of England was established; in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire it was Congregationalism, and the other states had none. There were many Catholics, Dutch Reformed, Quakers, Lutherans, and others living in the colonies that did not want to be forced to support any of the established churches. Thus it was not possible to get the newly freed states to agree to ratify a federal government that made one religion official.

Religions were the identity groups at the time of the founding and the First Amendment required their separation from government.

The phrase in the First Amendment, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” was a guarantee that no one would be taxed to support another religion, be forced to adopt the doctrines of another religion, or be prevented from pursuing their own religion. Religions were the identity groups at the time of the founding and the First Amendment required their separation from government.

As I have argued on this blog in November 2018, if today’s identity groups had been so prominent at the time of the founding, and religion was not the primary way groups of people with different beliefs were identified, the First Amendment may have, and should have, separated all identity groups from the state. From the pogroms in Europe, the beheadings in Arabia, burning “witches” and “heretics” at the state in colonial America, to the industrial killing of millions of Jews in Germany, identity group politics inevitably leads to structural violence if not genocide.

The ratification of the US Constitution, therefore, required the abolition of the identity group politics of the time. No one wants to be subjected to the whims or demands of some other identity group. Identity group politics is the enemy of the idea that all people are created equal and have a natural right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” However, new identity groups have emerged and evaded the literal interpretation of the First Amendment by calling themselves as names other than religions. Political parties have become the primary groups that have, over the years, established themselves in the US governments.

As I argued in August, 2018, party names on ballots are a method of embedding identity groups in government. People inevitably feel forced to vote for candidates endorsed by one party or the other, and not someone who represents them. The political parties are motivated to work for themselves and the wealthy lobbyists that pay them, not the citizens that vote for them—although they pander for votes at election time. Political parties can especially pander to other identity groups when they have identity group data to help shape policies that promise something to them from the general treasury. Such laws that “establish” such policies in favor of these identity groups violate the free pursuit of happiness of those others who foot the bill without their consent or genuine representation. This identity group legislation thus violates the basis of the principle of “all people are created equal” enshrined in the Constitution.

Civil Rights are Negative Rights

No one is sure why Thomas Jefferson chose to write “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” rather than the classical formulation of “life, liberty, and property” by John Locke. I suspect there was political pressure from abolitionists who considered it wrong to hold slaves as “property.” Also, Jefferson’s philosophical indebtedness to epicureanism and stoicism, and the writings of Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui (1694-1748) may have influenced his choice. The result of his selection was most fortuitous. Abolitionists could hold up this phrase in arguing that slavery denied some people this right and should therefore be abolished. Immigrants from all over the world say they came to America to pursue happiness, or to pursue their dreams.

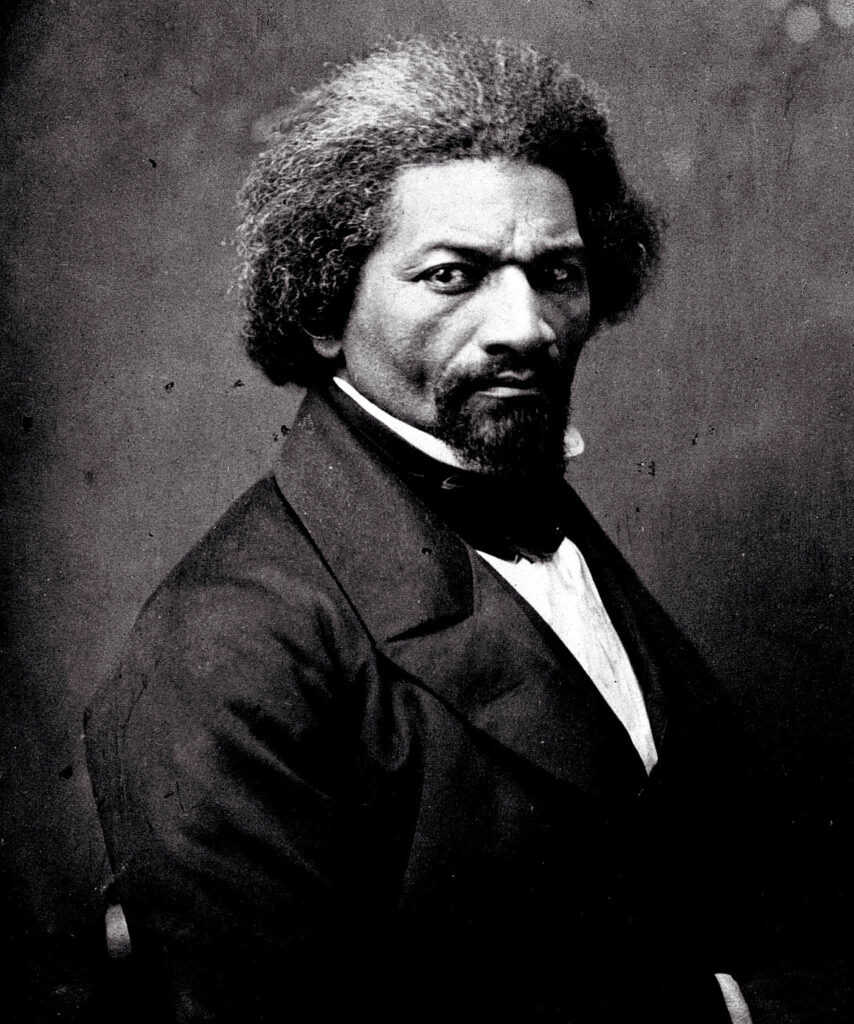

“Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” was also the goal of freed blacks and slaves in the US before the Civil War. They wanted to freely pursue their own dreams, and were willing to fight off slavery in the United States the way the colonists had thrown off their masters in England. No one expressed this view more forcefully than Frederick Douglas when he was asked what the government could do for him. His answer was “leave me alone.” In other words, he sought negative rights, as had the US Founders. The following passage from an 1862 speech indicates his strong views on this:

Let us stand upon our own legs, work with our own hands, and eat bread in the sweat of our own brows. When you, our white fellow countrymen, have attempted to do anything for us, it has generally been to deprive us of some right, power or privilege which you yourself would die before you would submit to have taken from you. When the planters of the West Indies used to attempt to puzzle the pure-minded Wilberforce with the question, How shall we get rid of slavery? his simple answer was, “quit stealing.” In like manner, we answer those who are perpetually puzzling their brains with questions as to what shall be done with the Negro, “let him alone and mind your own business.” If you see him plowing in the open field, leveling the forest, at work with a spade, a rake, a hoe, a pickaxe, or a bill—let him alone; he has a right to work. If you see him on his way to school, with a spelling book, geography, and arithmetic in his hands—let him alone. Don’t shut the door in his face, nor bolt your gates against him; he has a right to learn—let him alone. Don’t pass laws to degrade him. If he has a ballot in his hand and is on his way to the ballot box to deposit his vote for the man whom he thinks will most justly and wisely administer the Government which has the power of life and death over him, as well as others—let him alone; his right of choice as much deserves respect and protection as your own. If you see him on his way to the church, exercising religious liberty in accordance with this or that religious persuasion—let him alone.—Don’t meddle with him, nor trouble yourselves with any questions as to what shall be done with him.

Frederick Douglass, “What Shall Be Done With the Slaves if Emancipated?” (Monthly, January 1862).

A Civil War to Free the Slaves

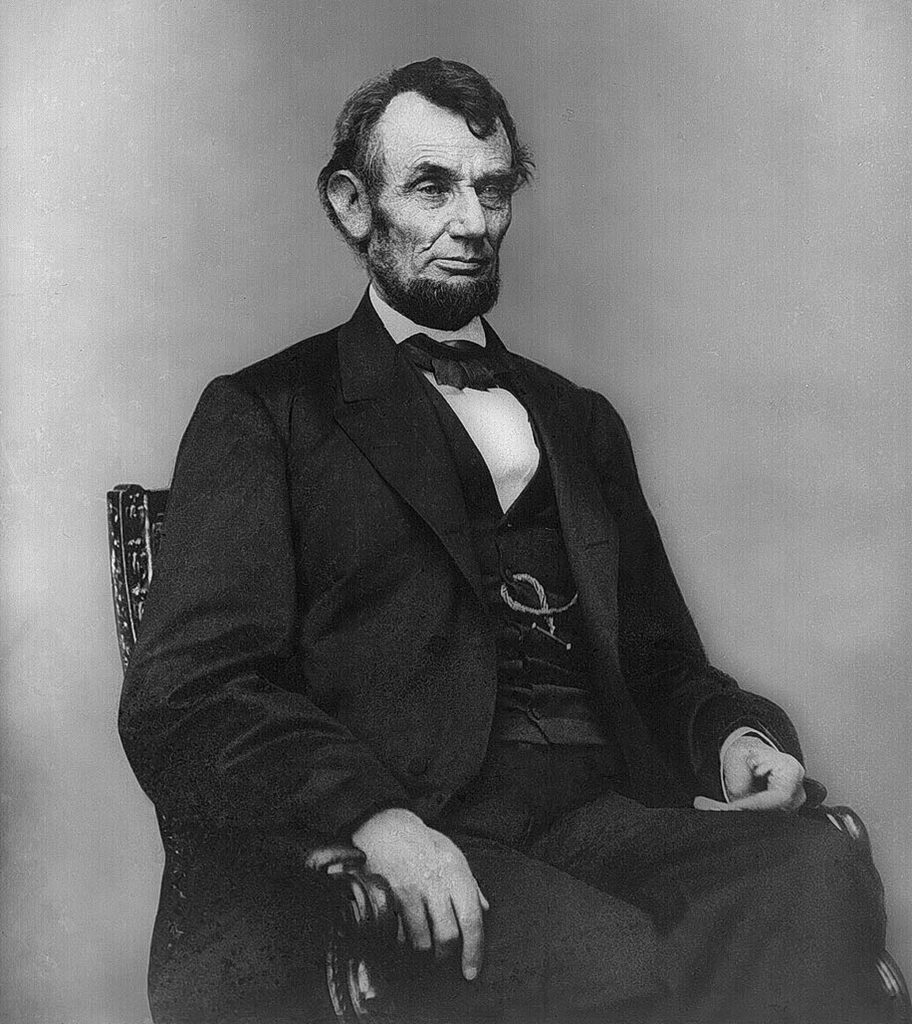

It is frequently pointed out that Abraham Lincoln (1) did not begin the Civil War to free the slaves, but to prevent the secession of the South, and (2) considered blacks in some ways inferior to Whites. Those arguments do not undermine the fact that he saw blacks as having the same unalienable natural rights the founders declared in the Declaration of Independence. His comments on the Dred Scott decision as a private citizen in 1857 make this clear:

[The founders] defined with tolerable distinctness, in what respects they did consider all men created equal—equal in “certain unalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This they said, and this they meant. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality,…

They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere. The assertion that “all men are created equal” was of no practical use in effecting our separation from Great Britain; and it was placed in the Declaration, not for that, but for future use. …

Abraham Lincoln, “The Dred Scott Decision and Slavery,” Springfield, Illinois, June 26, 1857.

The Civil War was been called “The Second Founding” by Columbia University History Professor and Pulitzer Prize winner Eric Foner. It was “a crucial chapter in the nation’s long and continuing struggle to realize the Declaration of Independence’s golden promise.”1https://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2019/10/19/unalienable_rights_reconstruction_and_constitutional_continuity_141538.html The “reconstruction amendments” were intended to extend the promise of America to all citizens. The 13th Amendment (1865) abolished slavery. The 14th Amendment (1868) established birthright citizenship and provided due process and equal protection of the laws for all persons. The 15th Amendment (1870) guaranteed that the right to vote could not be denied on the basis of race.2Ibid.

Reconstruction involved reorganizing Southern state governments along Republican principles of equality and integration. Federal money was provided to integrate railroads and other facilities. But reconstruction was resisted and messy. A policy to give every freed black “40 acres and a mule” was reversed by Andrew Johnson after Lincoln was assassinated. Corruption was rampant with the misuse of federal funds.3https://www.britannica.com/event/Reconstruction-United-States-history Some Democrats accused Republicans of instituting “Black Supremacy” laws. By 1870 all Southern states had been readmitted to the Union, but the Democrats had organized the Ku Klux Klan to intimidate voters and terrorize Republicans. By the end of the 1870s, blacks were politically free but segregated. Jim Crow laws were enacted by Democrats that discriminated against them. Between 1882 and 1967, 4,743 individuals were lynched, 3,446 blacks and 1,297 whites.4Sandra K. Yocum and Frances Presley Rice, Black History 1619-2019 (Saint Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2021), p.266. As the sale of land was denied to blacks, many returned to their former masters to work for wages, or worked the land as sharecroppers. Those seeking greater freedom moved to cities or the North.

Desegregation as the Third Wave of Civil Rights

Freeing the slaves through a Civil War did not solve the question of segregation vs. integration. Even though the Declaration of Independence declared “all men equal,” races (and sexes) were treated differently by state and local laws.

The Supreme Court, rather than strictly following the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, has often sided with majority views. This was the case in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, when the Supreme Court decided 7-1 that “separate but equal” facilities were legal. The case stemmed from an incident in which African American passenger Homer Plessy refused to sit in a train car for blacks. After sixty years, two world wars, and integration in the North public opinion had changed.

In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Thurgood Marshall, the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, served as chief attorney for the plaintiffs. The justices were divided on how to rule on school segregation, with Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, a Democrat, holding the opinion that the Plessy verdict should stand. When Vinson died, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower replaced him with Earl Warren, the Republican governor of California, the balance shifted toward desegregation.5https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka Warren wrote that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” as segregated schools are “inherently unequal.”

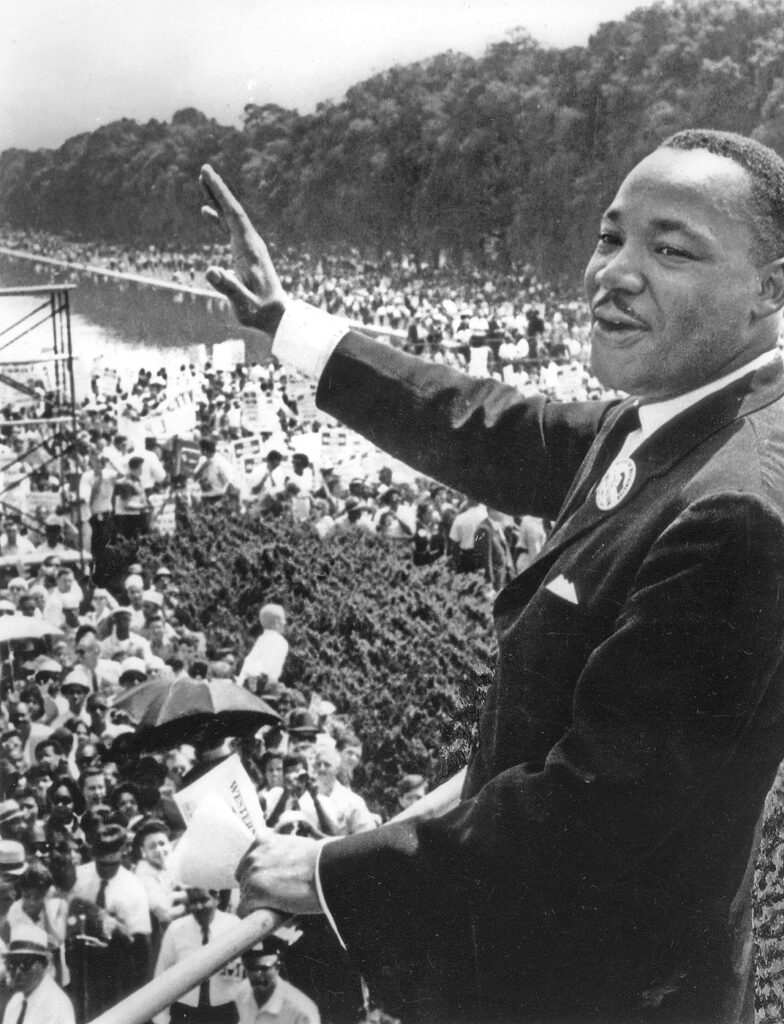

Brown v. Board of Education led to backlashes that required U.S. Marshals to enforce allowing black children to attend all-white schools. But the decision did not end other aspects of segregation like transportation, restaurants, or bathrooms. Progress in this area was made under the leadership of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., with sit-ins, protests, and marches. Following the example of Mohandas K. Gandhi in India, King won over the hearts of those who feared violence with love or satyagraha as the basis of his activities. He asked for equal rights, not retribution or racial hatred.

King’s tactics exposed the violence on the part of the remnants of the KKK and the police who used water hoses. The majority of the population sided with King. In a nationally televised address on June 6, 1963, President John F. Kennedy urged the nation to take action toward guaranteeing equal treatment of every American regardless of race. Civil Rights legislation was passed in 1964, forbidding discrimination on the basis of sex, race in hiring, promoting, and firing. It was followed by the voting rights act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. It took a century after the civil war to legally and economically end segregation.

Colorblindness as the Fourth Wave of Civil Rights

One of the most powerful and memorable speeches in United States history was Martin Luther King, Jr’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the Washington Monument on August 28, 1963. This speech sealed the fate of the Civil Rights legislation, which Lyndon B. Johnson signed when he saw the country, including the mainstream media, overwhelmingly supported it:

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “I Have a Dream,” August 28, 1963.

The majority of Americans believed the 1960s Civil Rights legislation had completed the long road to the achievement of the “American dream” King had spoken of. Schools and businesses were integrated, intermarriage accelerated, and Americans became increasingly “colorblind.”

But racism was not completely eradicated. While the majority of society was bent on integration and “judging people by the content of their character and not the color of their skin” as the cultural norm, many people found “playing the race card” could be used for personal wealth, power, or political goals. Social activists, NGOs, and politicians discovered that the wounds of racism could be reopened in the name of “anti-racism” that lingered in society and remained embedded culture, social institutions, and the psychology of individuals. Most Americans sense the truth in this lingering racism and want to see it completely eliminated. However, the policies to solve the problem of cultural racism proposed by the Democrats and Republicans couldn’t be more different.

Democrats want to identify people by color, teach “sensitivity training,” pass affirmative action laws that institute quotas based on race, teach “white guilt” in public schools and workplaces, and promote “reparations” from the federal treasury to black individuals or identity groups. On nearly every social issue, from poverty, school test scores, employment, and the recent pandemic, they break down the issue by race. This requires government databases and reports to classify disparities based on race. And, the conclusions drawn from these reports inevitably find racial disparities responsible for the problem with a government grant or new agency to study the problem the solution.

These policies would be opposed by Frederick Douglas who argued “let us stand upon our own legs, work with our own hands, and eat bread in the sweat of our own brows,” or Martin Luther King, Jr’s, “dream” for race to be removed from public policy. Republicans generally want to complete progress towards civil rights by completely ending government policies that treat whites and blacks differently in any way. They view identity politics as skin deep political pandering and the newest form of racism hiding under the language cloak of “anti-racism.”

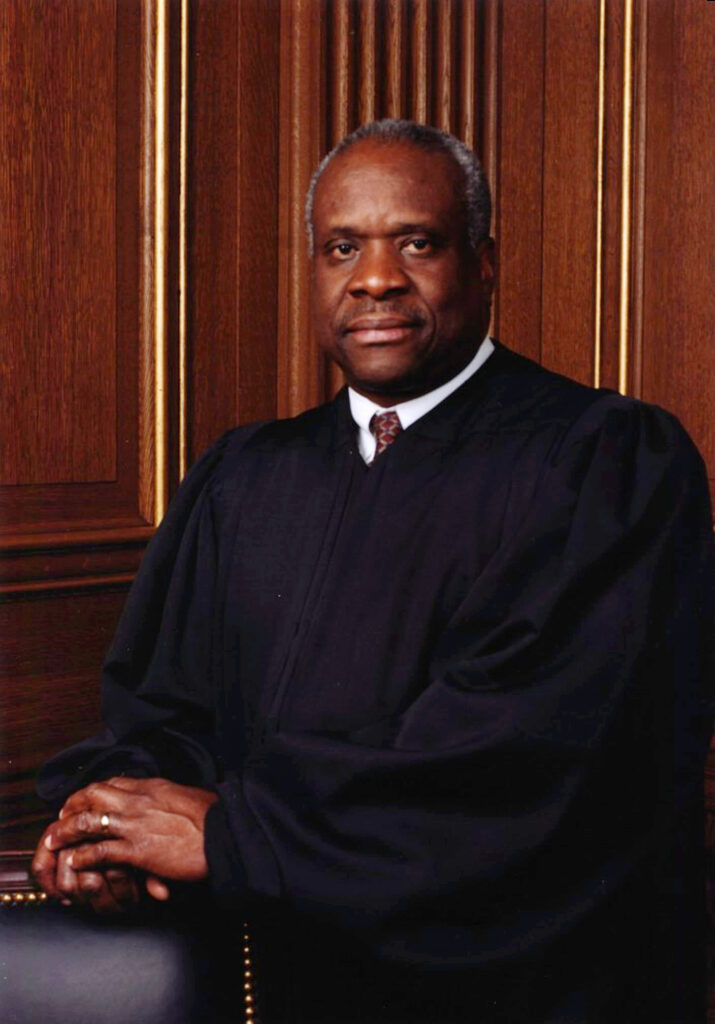

The Supreme Court has now been confronted by “colorblindness” question, with Justice Clarence Thomas siding most strongly with this interpretation. In Adarand Constructors, Inc., petitioner v. Frederico Pena, Secretary of Transportation, et al., Thomas wrote:

Purchased at the price of immeasurable human suffering, the equal protection principle reflects our nation’s understanding that [racial] classifications ultimately have a destructive impact on the individual and our society.6https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/93-1841.ZC1.html

In a Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, et. al., which regards affirmative action Thomas wrote:

The Constitution does not pander to faddish theories about whether race mixing is in the public interest. The Equal Protection Clause strips States of all authority to use race as a factor in providing education. All applicants must be treated equally under the law, and no benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify racial discrimination.7https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/11-345

While Thomas has been attacked for his policies by both politicians and high-profile journalists, his arguments describe the completion of the goals of civil rights and an end to racism. In his writings, Justice Thomas describes why affirmative action, identity politics, and reparations policies continue to divide Americans and hurt both blacks and whites. He understands that when people are given jobs or other things (positive rights) because of their skin color, they don’t know whether they deserve them, or are inferior. He believes such programs treat black people unequally because they are viewed by providers of such programs as inferior because of their skin color. This is a new form of racism hiding under a cloak of anti-racism.

Conclusion: Colorblindness and Laws Against Data Collection and Government Reports Based on Color

The civil rights legislation in the 1960s gave full legal civil rights protections (negative rights) to all Americans regardless of race, sex, or religion. However, positive rights legislation that treats people differently based on the color of their skin has not been eliminated. This is a more subtle version of the segregation vs. desegregation issue debates from the Civil War until the 1960s. Identity politics are a form of segregation that treats people differently based on racial or other forms of social identity and not as individual citizens with equal treatment by the law.

Today Justice Clarence Thomas stands in the tradition of Frederick Douglas in 1862 and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1963 in paving a judicial path for black Americans to achieve the American dream. His opponents tend not to want blacks to achieve this dream and would prefer to use political power to achieve their own ends. Thomas sees positive rights based on race as unconstitutional.

The collection of public data by race, and the issuance of government reports by race, has become the latest form of structural racism and corruption. Race is used as a divisive lobbying tactic. Government funds are thus funneled to people promising to act on the behalf of disadvantaged groups, without addressing the actual needs of individuals.

Outlawing the collection of data by race and the use of such data in government reports would complete the 400 year path of African-Americans from slavery to full equality under the law. This evolution of civil rights in American can be considered in four phases (1) the founding proclamation in the Declaration of Independence, (2) the Civil War and freedom from slavery, (3) the court decisions Civil Rights laws in the 1950s and 1960s that ended segregation, and (4) the yet-to-be achieved principles of colorblindness that remove all distinctions based on race from social institutions. Phase four’s approach through identity politics mirrors phase three’s approach through segregation. It is a way for racism to get transformed after the previous form was eliminated.

It took one hundred years to replace segregation with desegregation. Hopefully, the United States will not suffer that long in replacing identity politics with full integration.

Comments

Completing Civil Rights: Ending Structural Racism by Removing Race from Institutional Data and Policy — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>