Is Race or Student Motivation the Highest Correlate to Student Failure?

In many policy discussions about the “achievement gap” between whites and minorities in public schools, racism and insufficient public funding of schools are frequently given as the primary reason for the gap. But is blaming race or schools getting to the heart of the achievement gaps that exist today? Or, are social factors related to the motivation and preparation of students more important than either of these policy-driven reasons?

Most Public Schools are not Consciously Racist

While some individuals employed by public schools may be racist, and some subconscious racial practices may still exist, racist laws related to segregation and civil rights are largely a thing of the past. Further, the increased diversity and intermarriage in urban American melting pots has tempered old racial stereotypes. Especially government laws and inner-city school policies have consciously strived to eliminate racism from schools over the last 50 years, and often extra programs are funded to help failing students catch up to others.

Yet, newspapers continue to report that inner city public schools experience greater delinquency and lower performance among racial minorities. And, for at least the last thirty years, legislators have tried to address the achievement gap by earmarking extra funding for public schools in inner cities. However, performance disparities have not improved; if anything the “achievement gap” is widening. Are minorities failing because of their race, or are other reasons like socialization of children more important?

Government Statistical Practices Promote Racial Stereotypes

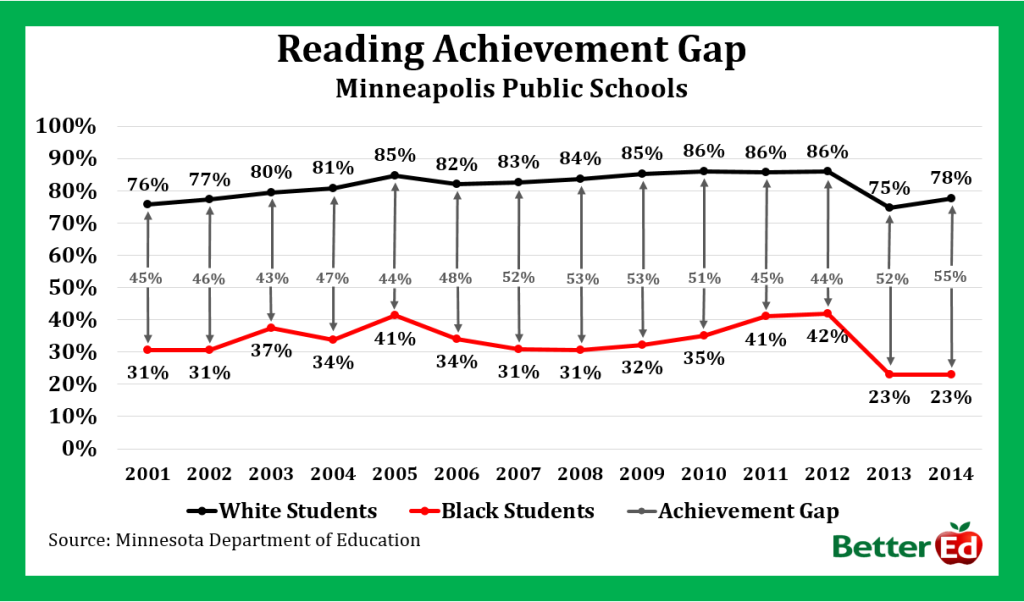

Social scientists can study whether race, or racism, is the strongest correlate to student failure or whether there are other factors. Because of the tragic history of slavery in the United States, statistics are often promoted racially. When schools are asked to report to governments on student achievement, they are asked to report them by race. So charts based on statistics from departments of education get generated like this:

On the above chart “race” is the only correlate to the achievement gap. As a result, it is natural for people to assume that race is the reason for the achievement gap. One reason charts like this appear is that government statistics departments categorize people by race and ask people to indicate their race on questionnaires. Besides age and sex, race is one of the most frequently asked questions on government forms.

But is race the primary reason people succeed or not? The answer is no. Paradoxically, the racial questions on many government forms are asked because of the history of racism in the U.S., and good intentions for the data they collect. However, when race is the only publicized correlate to a social concern, it is not only misleading, but promotes racial stereotypes, and itself can become a racist practice. These government statistical practices and media reporting of these statistics by race continue to promote racial stereotypes, even though most citizens and schools are trying to move racism into the past.

Blaming Racism on the Achievement Gap Misses Other Important Reasons

There are many reasons children do not succeed in school. We are increasingly becoming aware that poverty, lack of positive role models in early childhood, and other social factors also correlate with preparation and motivation for children to succeed in school.

In a recent Star Tribune front page article, Mitch Pearlstein argued that racial prisms have been blinders:

It’s difficult to think of anything less likely to improve education in general and the achievement of minority and low-income children in particular than ceaselessly dwelling on race. For how many decades has virtually every issue in Minnesota and American education been funneled through prisms of “diversity” and “multiculturalism”? And for how long have such preoccupations been party to not nearly enough kids learning how to read, write and compute adequately?

Government reporting requirements focus us on race, and not other important social factors, like the education young children get in their homes. These factors are cultural and not legal. And governments are not structured to address these concerns.

Blaming School Personnel Does Not Address the Achievement Gap

Another reason often given for the achievement gap is the poor quality or financing of inner-city schools. Even though such schools often receive extra funding today, they have more student failure and truancy. There are legitimate concerns about high teacher turnover and many young teachers starting out in inner-city schools then move to other schools where more students achieve higher scores. This turnover of teachers often leaves inner-city schools at a disadvantage in teacher experience compared to other schools, but within these schools the achievement gap still exists, meaning that neither teacher quality nor amount of funding per student are highly correlated to student failure.

Blaming school teachers and administrators, like blaming race, again misses the mark. It too, may be an attempt to escape real, and the more difficult to address, social reasons for the lack of student preparation and motivation that occurs before students ever go to school.

Student Preparation and Motivation

Student preparation and motivation are more important for student success than their race. It is essential to develop more statistical data on other social factors that correlate with student success: family makeup, household income, parent employment history, social affiliations, and spiritual education. Students do not come to schools as blank slates, having equal motivation to learn. While, we live in a pluralistic society and accept people of all cultural and social backgrounds as equally valuable before the law, this does not mean that all social values and practices, or lack thereof, equally prepare students for school. The amount students read at home, and the attitudes towards education, work and success of the adults and peers in their community, greatly impact how prepared and motivated students are when they get to school.

Student preparation for school is increasingly considered to be the primary correlate to student success. Here is a brief quote from a 2010 Psychology Today article:

It’s easy to compare successful and failing schools and see the obvious differences in facilities, resources, and support. But these “causes” of public education’s problems have blinded us to the real difference, namely, how prepared students are to achieve academic success. The majority of students in “good” schools are prepared to learn when they enter the public-school system while most students who attend “failing” schools are not.

Research has shown that low-income parents use fewer words with their children on a daily basis, engage in less bidirectional conversation, and expose their children to books and reading far less often compared to middle- and upper-income parents. These differences in early childhood experiences between these groups of children are striking and demonstrate why failing students are the problem. It seems clear enough: schools are failing because they are trying to educate students who are not prepared to learn. (Psychology Today, April 2010)

The Secular Nature of Public Schools makes Learning of Values at Home More Important

The nature of secular non-religious schools, which public schools are by definition, means they are unable to promote spiritual values, like the value and purpose of one’s life, because they have to respect the separation of church and state. Seldom are the values promoted by various religious groups studied or even mentioned by public school teachers, perhaps more out of fear of offending someone, than out of a desire to teach students how to compare the values of other students with one’s own. This should normally begin in middle school, when children naturally begin comparing and developing their own identity.

Public schools tend to focus on the value of knowledge and skills to earn enough money to live on, but it is hard for a public school teacher to talk about ultimate meaning and purpose. Motivation often comes from such ultimate or spiritual values. In traditional societies and communities, these values are inculcated from birth. However, students from dysfunctional homes, or immersed in communities that emphasize “gaming the system,” rather than becoming a responsible producer and citizen, will likely attempt to “game the school,” rather than study and do homework.

This is one reason many private schools, centered on some value system, religious or other, have more success than public schools in improving the motivation of students who were not provided it in their homes and communities in pre-school years.

Research on the effectiveness of private schools when it comes to low-income and minority children — routinely conducted by top-tier scholars with strong ties to Harvard and Stanford — is clear and encouraging. But putting aside increased test scores and graduation rates, recall how the late John Brandl, a former DFL state legislator as well as dean of the Humphrey School of Public Affairs, used to write and speak about how private and religious schools provided “some disadvantaged students with a substitute for the care they are not receiving from family and neighborhood — something possible but very rare in public schools.” (Pearlstein, op. cit.)

Pluralism and Public Values

The problem of consensus on general or universal values in a pluralistic society is one of the core problems of our contemporary Western world. Public schools, unable to teach a set of positive functional values, tend to focus on equal rights and justice. But such values can only correct problems of unequal treatment before the law, and cannot address how people with those rights can succeed. Private schools are better able to teach about responsibilities and often refer to classical virtues, sacred scriptures, or experimental frameworks. But these values are generally considered arbitrary and not universal by contemporary society.

It is more common for our secular society to remove public monuments that display traditional teachings about moral behavior, like the Ten Commandments, attached to a particular civilization, than to celebrate the diversity of these teachings and ask “Why were those commandments valuable to the societies in which they were practiced? How can universal values and responsibilities be more scientifically understood and accepted in the contemporary world?

Universal human values, to the extent they become widely accepted today, are those promoted by universities and social elites, not religions. However, universities have focused on equal justice and human rights, not on human responsibilities necessary for a functional and happy society. But rights and justice, without responsibility, are an inadequate set of values to support a social system. Most people sense this. It causes psychological tension—and leads to reactionary backlashes or revolutionary hopes that government can replace cultural responsibilities. Neither approach is adequate to address the motivational factors behind the achievement gap in public schools.

Social Scientists Can Develop More Universal Standards

While social scientists can, through statistics, explain what social factors produce desired social results, like success in schools, they have not adequately done so. Rather than asking questions like “What factors most strongly correlate with a social outcome?” twentieth-century sociologists, in the early phase of development of their disciplines, tended to ask “what is ‘normative’ behavior?” “Normative” merely described how people were behaving, and not whether that behavior led to long-term personal happiness or a functional society. If anything, “normative” became a lowest common denominator that steadily deviated from the behavior required for human happiness and social well-being.

In the 21st century, social scientists should be looking more at primary correlations between social factors and desired outcomes, asking questions like “What social factors most strongly correlate with student success or failure?” Answers to these questions will be far superior and less divisive than government reports that display student achievement by race. Then our society, rather than asking legislators to pass a law which would only limit negative behavior, will be in a position to teach positive values and responsibilities in public schools, while keeping separation of church and state intact. These values will not be justified by tradition or scripture but by scientific methods that can eventually become accepted by everyone.

Gordon’s article is well-done and informative, as always.

The one sociological concept that comes to mind is James Coleman’s by now familiar idea of SOCIAL CAPITAL:

We live in a highly stratified society, in which success and privilege on the one hand, and poverty and failure on the other, are transmitted from one generation to the next, ad infinitum. For example, blacks as a group have not progressed relative to whites over many generations. We call this the “reproduction of inequality.”

Gordon is absolutely right that the core of this phenomenon – the reproduction of inequality – is rooted in the sphere of EDUCATION.

The reason for this is the absence of social capital in the underclass. There is simply not a CULTURE, a value system, a system of HABITS that emphasize the value of education.

The absence of social (and cultural) capital in the underclass is a less tangible but equally important form of poverty. The presence of it is evident in such communities as Jews and Asian-Americans, groups which value education even for its own sake. The transmission of this “capital” occurs from generation to generation in some communities, even those that are not necessarily terribly wealthy in a purely financial sense. Elsewhere, success among the young remains elusive because parents, adults, the community at large lacks social capital. This form of poverty is by no means limited to African-Americans. It also characterizes millions of lower-class whites, both rural and urban.

Thanks Tom, Just to clarify a bit, when you says “blacks as a group” or Jews and Asian Americans as groups, you are referring to a norm for a group that ends up producing stereotypes of groups. Nevertheless there are exceptions to these norms, and some blacks are highly successful, while some Jews live in poverty. The reasons for this are not their Blackness or Jewishness, but individual social capital depending on the homes and communities they were raised in.